Our HIV clinic was flooded last week.

One learns to expect rain in the rainy season, but the downpour on the weekend saw much of Dili under water.

By the time I had sloshed my way into work on Monday, my ultra-efficient team had already dispatched most of the mud. We were open for business again by 10 o’clock.

The flood was not without casualties, though.

Our expensive, impossible-to-find-in-Timor filter paper met a sad fate. This special absorbent paper allows us to send blood samples to Australia using a technique called a dried blood spot.

Visitors passing through our office are generally conscripted to act as carrier pigeons, transporting these bits of paper to our Fairy God-Laboratory (the HIV Reference Laboratory, at St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney).

Dircia rolls up her trousers and gets the job done

HIV treatment decisions can be complicated at times, and our ability to access specialised drug resistance testing for our Timorese patients is an enormous advantage.

One day we hope this kind of testing will be available in Timor Leste, but meanwhile we continue to be grateful to our generous St Vincent’s colleagues for their help.

The other flooding casualty was our poor drowned garden, mired inches deep in mud.

We rely greatly on these few square feet of plant-filled courtyard. If we have a fraught patient, perhaps with a new diagnosis of HIV, we take them to the garden. (I take myself there sometimes, during my own fraught moments.)

From my perspective, the major attraction of the garden is that it protects my team from TB. Sitting safely in the open air, we can spend as long as we like talking with coughing TB patients, without worrying about picking up the infection ourselves.

Since the garden is now a swamp, we’ve had to see these coughing patients inside the clinic. Frustratingly, the N95 masks that provide us with protection from TB have been stocked out for many weeks. Several thousand masks wait in the central warehouse a few kilometres down the road, but an impenetrable array of red tape lies between them and us.

Stock-outs feature heavily in our day-to-day lives here. I’ve been scouring the supermarket aisles for Milk Coffee biscuits for weeks, to no avail.

Although being deprived of biscuits is undoubtedly bad, there are worse things to stock-out of (some might disagree).

For a while we existed uneasily as an HIV clinic without any HIV medicine. And although handing out drugs is not our team’s sole function, these life-saving tablets are certainly at the core of what we do.

Six months ago, people talked about stock-outs and heavy rains with exactly the same sense of inevitability. Why make a fuss? These things are part of life.

Just maybe, things might be changing.

This morning, Dr Alfredo talked with a colleague in Pharmacy, explaining that it was quite difficult to give good patient care when he had no paracetamol, or penicillin, or fluconazole (our most pressing shortages this week). Our team had recently discussed strategies for reducing the risk of stock-outs, some of which Dr Alfredo now shared.

Dr Alfredo’s excellent communication skills at work, this time with a patient

Apparently, he was compelling.

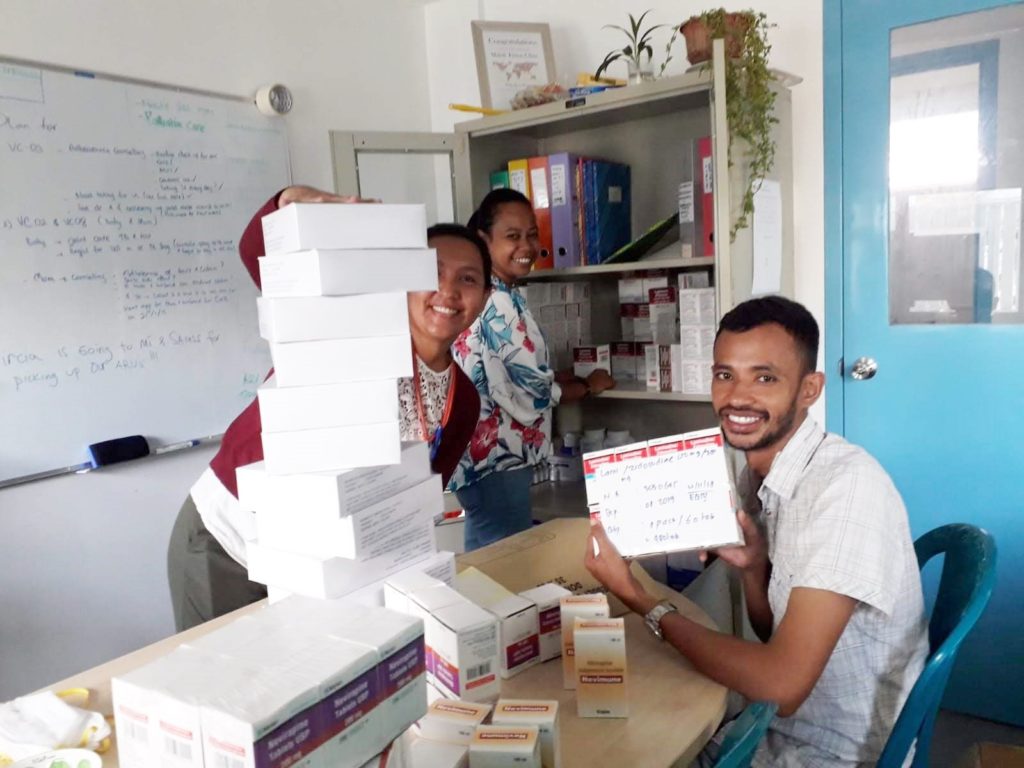

I came back from lunch to find something unprecedented. Sitting on the table was a big brown box, brim-full of everything we had asked for. Even the N95 masks were there.

Now, if only we could do something about the biscuit problem…

Dr Eleanor is supported by AVI